A couple of times I've mentioned here a classic and very scarce Isle of Wight book, the privately-circulated 1914 Almost Fairyland: personal notes concerning the Isle of Wight, written by John Morgan Richards, the American ex-pat businessman who retired to Steephill, near Ventnor. I'm pleased to say that I finally got to read it.

And you can too. It's finally been digitised by the Google Books Library Project, from the Bodleian Library's copy, and is available online with a Creative Commons "CC BY -NC -SA 2.0" license, which basically means you can do more or less what you like with it, as long as you credit the source, indicate any changes made, and make no commercial use of it. There are times when I'm in awe of what's available online, especially now that major libraries are embracing non-traditional CC models for controlled free distribution, as opposed to expensive print-on-demand models.

Almost Fairyland - dedicated "to past, present, and future visitors and residents of the Isle of Wight" - is a compilation of pieces originally written by Richards for the Isle of Wight Advertiser, Ventnor. It's not, unlike many Isle of Wight accounts, a me-too collection of well-known topography and history, but personal recollections of his 40 years visiting, and later living on, the Island.

He says "I am aware that the ego is present on every page". It sure is. It starts off innocently enough with a Victorian TripAdvisor-type account of his first visit with his wife Laura and their young family in 1872 ...

Once you filter out all that, Almost Fairyland is an often interesting account of the personal, social and political events among the Ventnor elite in the late 19th century. Richards was a close friend of another incomer, the chemical magnate William Spindler, and both had a lot of ideas for Ventnor, which Ventnor collectively was largely tardy to carry out. Spindler got a lot of useful stuff enacted: developing a water supply for Whitwell, improving St Rhadagund's Church, building a new road off the escarpment avoiding the dangerous Whitwell Shute, and laying out Ventnor Park and Gardens. But he got fed up, writing a vehement A few remarks about Ventnor and the Isle of Wight aimed at the reluctant Ventnorians, and took his ball home to work on (unsuccessful) plans to develop St Lawrence. Richards writes:

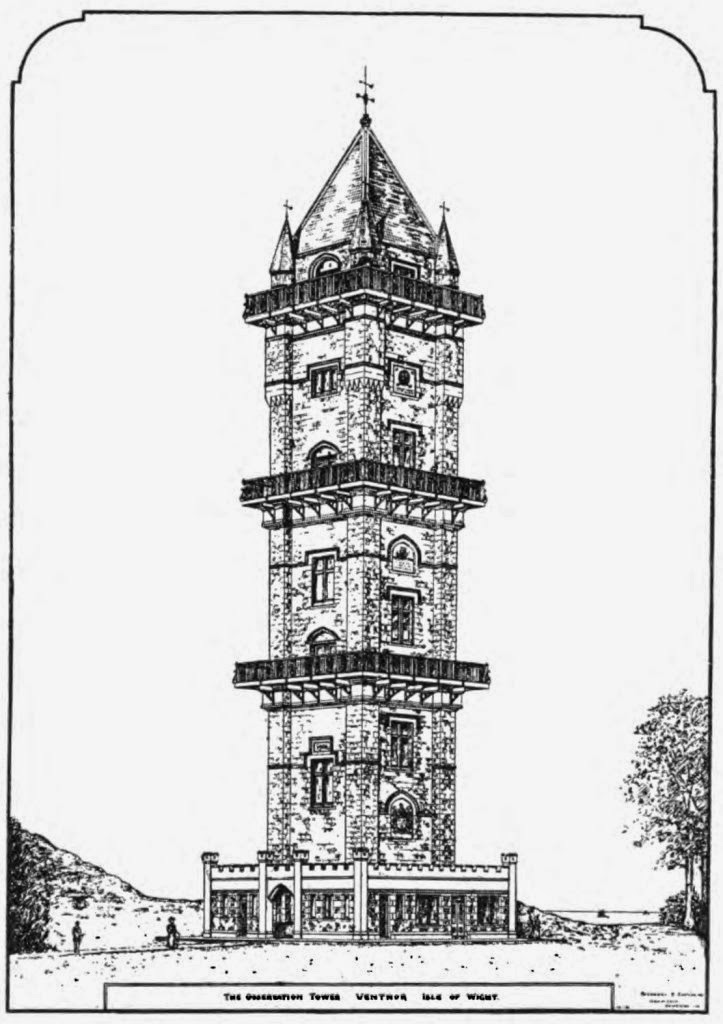

Richards' own concepts for Ventnor and the Wight, expounded in the book, included an ObservationTower with passenger lifts and staircase, improvement of the golf course, a Lift or Funicular Railway to the top of the Downs, plans for an Undercliff Cottage Hospital, and the still-extant concept of an Isle of Wight Tunnel to the mainland. The unfeasibility of the tower, built on the Undercliff landslip geology known to be majorly unstable even in Richards' day, is mind-boggling.

Other points of interest include a good deal of detail on the history of Steephill Castle; Richards' reaction to national and international events such as the Boer War, the sinking of the Titanic, and the 1912 coal strike (when Mrs Richards - who believed she had a hotline to high places - sent daffodils to the Prime Minister); and Richards' meetings with celebrities such as the Island hymn writers Albert Midlane and Mrs Jemima Luke, Mark Norman (the lugubrious fishmonger geologist), the painter Herbert Schmalz, Harry De Vere Stacpoole, the novelist Helen Mathers, Spindler's artist son Walter (who unsuccessfully courted Richards' novelist daughter Pearl), and of course Pearl Craigie herself ("John Oliver Hobbes").

At the level of personal impression, I can't say I like Richards' narrative voice. It's generally very impersonal, and - though I'm probably not one to criticise this - he's an information bore with a complete lack of affect. For instance, his reaction to the Titanic disaster is largely to go into a litany of statistics about other liners: tonnage, coal burned per day, etc etc. And he airbrushes out any personal complexities; he goes on about his daughter's writing career and her marriage to "Mr Craigie", but there's no hint of her acrimonious divorce.

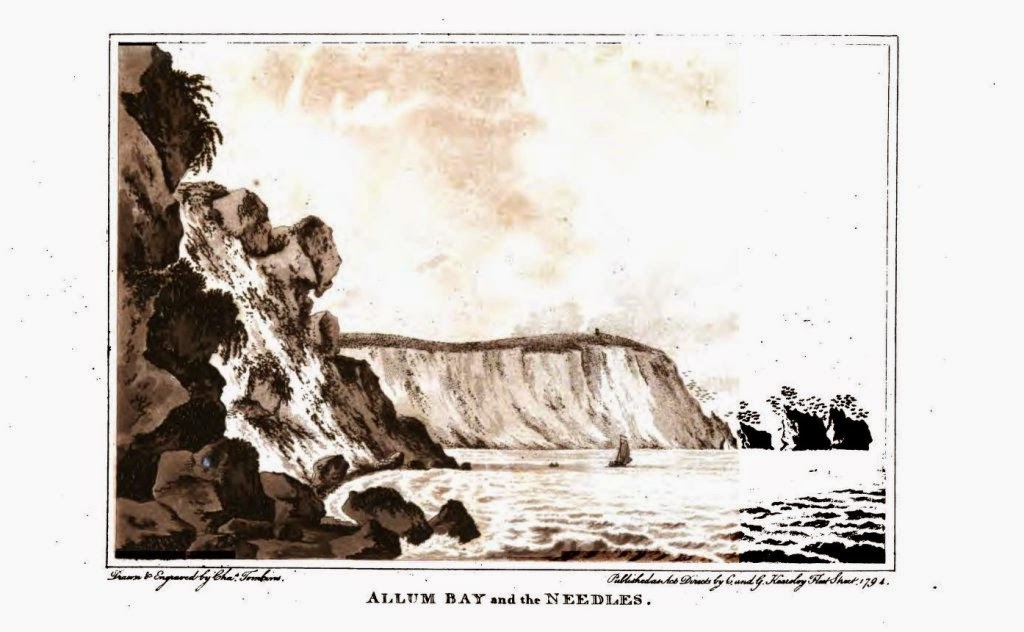

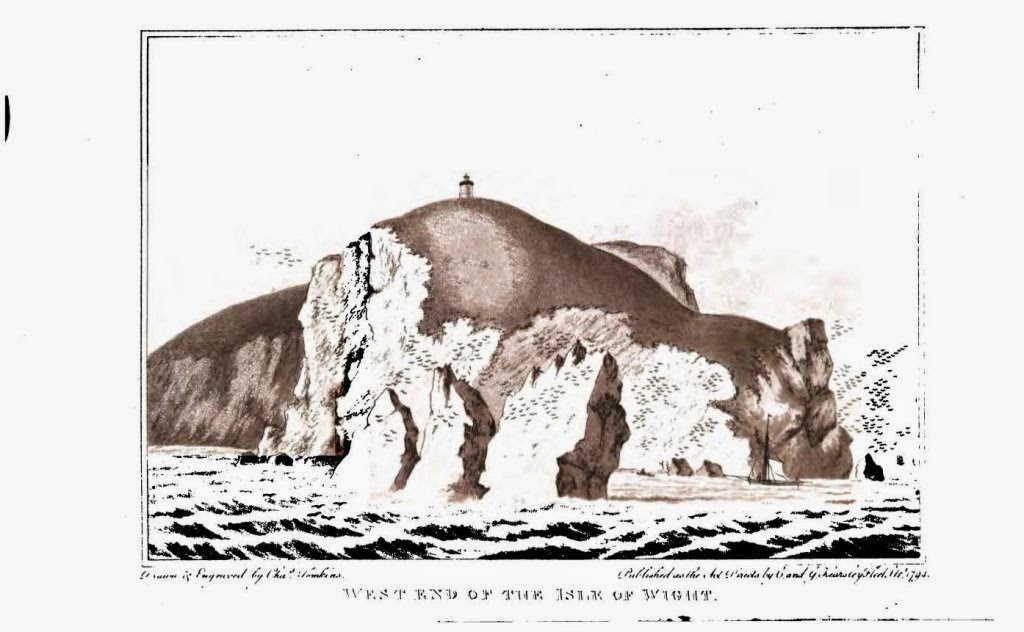

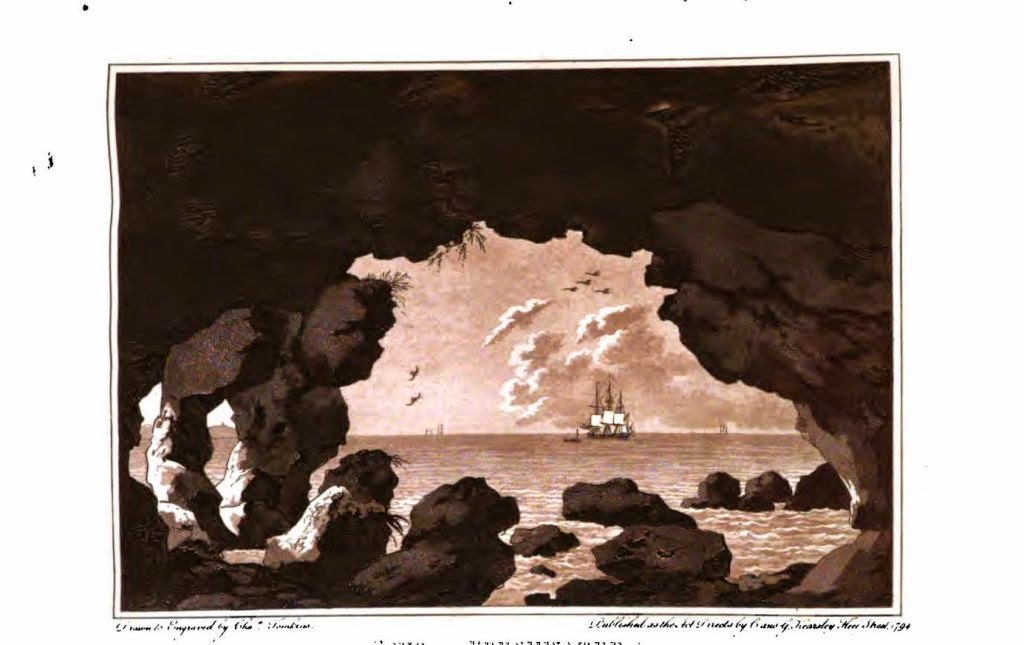

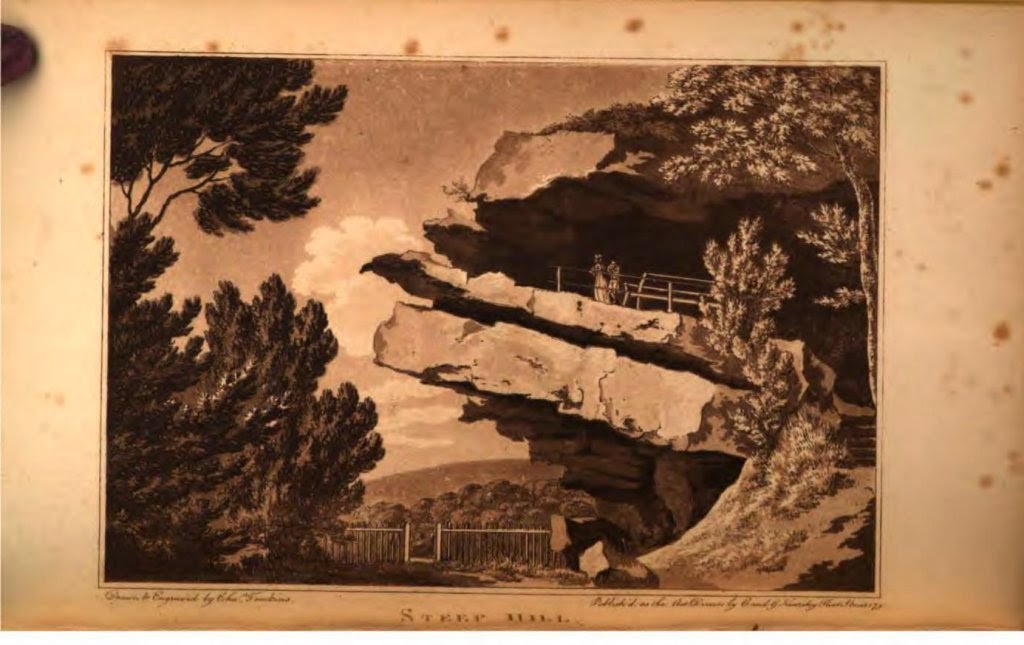

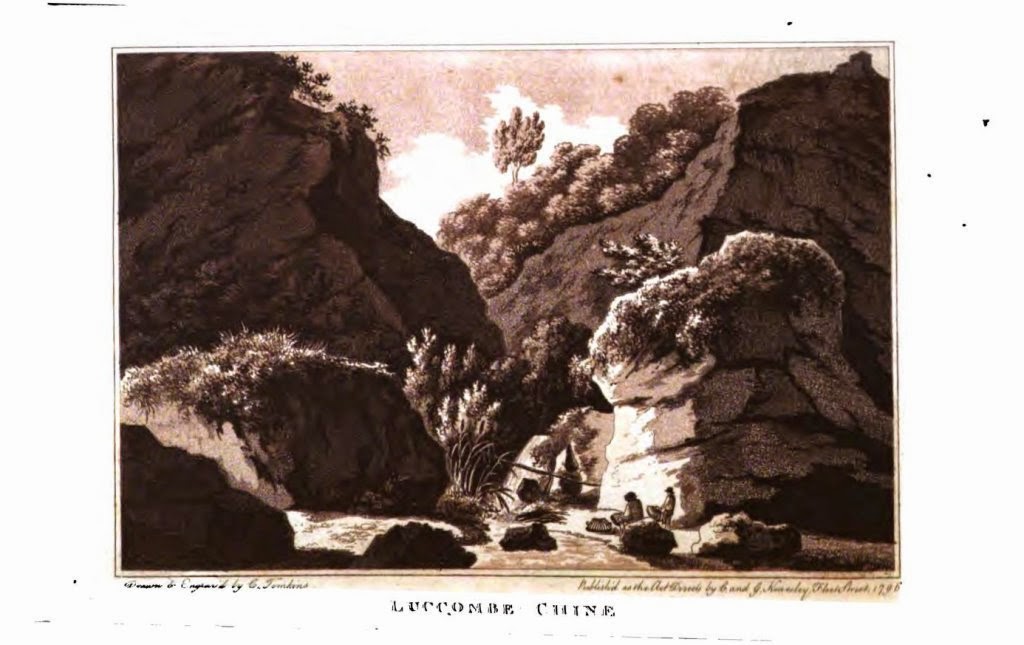

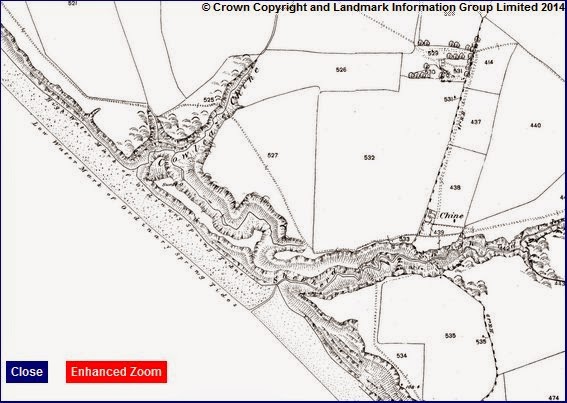

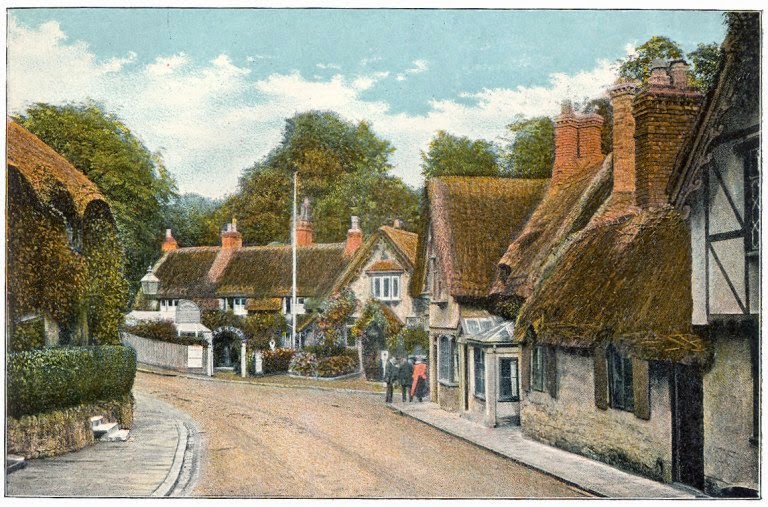

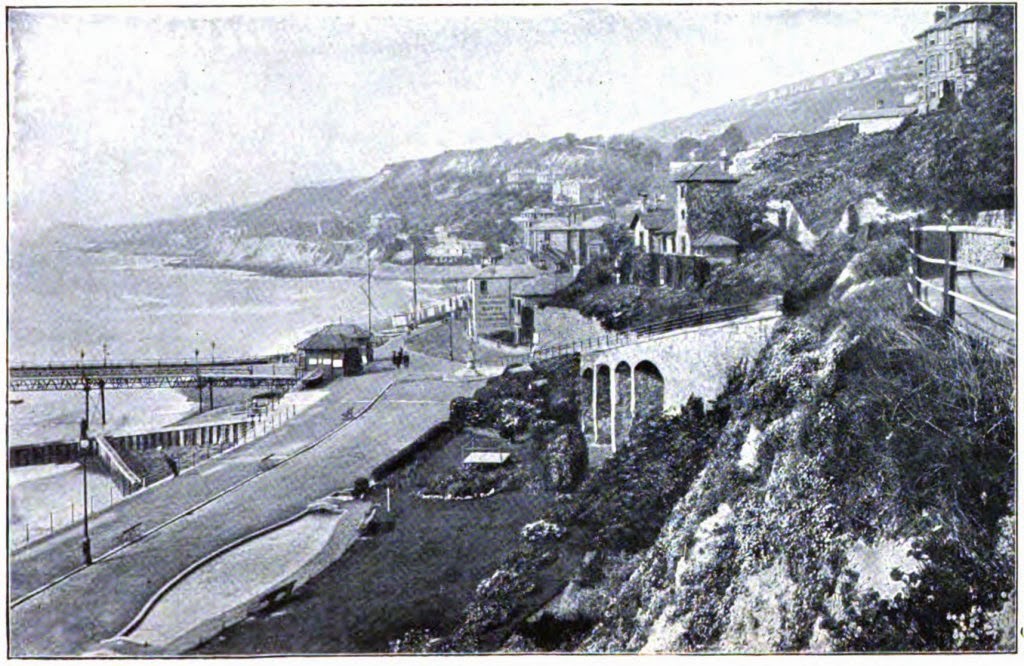

Almost Fairyland is illustrated with 53 monochrome plates. I rapidly spotted - compare and contrast ...

... that the majority of general topographic scenes are ripped from, or from the same source as, the 1910 Jarrold & Sons Pictures in Colour of the Isle of Wight (Project Gutenberg #17296), so you can see those there. Here's a further sampler of the remainder:

Almost Fairyland, personal notes concerning the Isle of Wight (Richards, John Morgan, London: John Hogg, 1914, 53 plates, 184 pages). Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0: England & Wales (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0) licence.

You can access it through the Bodleian's catalogue - Aleph System Number: 014642324 - or through this slightly more convenient Europeana portal: Almost Fairyland, personal notes concerning the Isle of Wight.

- Ray

And you can too. It's finally been digitised by the Google Books Library Project, from the Bodleian Library's copy, and is available online with a Creative Commons "CC BY -NC -SA 2.0" license, which basically means you can do more or less what you like with it, as long as you credit the source, indicate any changes made, and make no commercial use of it. There are times when I'm in awe of what's available online, especially now that major libraries are embracing non-traditional CC models for controlled free distribution, as opposed to expensive print-on-demand models.

Almost Fairyland - dedicated "to past, present, and future visitors and residents of the Isle of Wight" - is a compilation of pieces originally written by Richards for the Isle of Wight Advertiser, Ventnor. It's not, unlike many Isle of Wight accounts, a me-too collection of well-known topography and history, but personal recollections of his 40 years visiting, and later living on, the Island.

|

| Three generations of the Richards family Crop of Bodleian Library 014642324 e-text. Licensed under Creative Commons CC BY -NC-SA 2.0: England and Wales. No commercial re-use. Any re-use must follow same license. |

seeing the hill-sides of the four G's, viz. the 'Glorious Glory of the Golden Gorse'... and being amazed by the practice at their Belinda House lodgings of ...

the heating of the water in the tea urn after it was brought to the table by dropping... and goes on via some pleasant personal detail, such as his experiments in growing maize, his pride at his son Norris's canoe expedition circumnavigating the Island, and his exasperation at regularly getting a circular letter objecting to his right to vote (which he neither had nor desired, choosing not to naturalize). But as the book proceeds, it goes into an accelerating gush of name-dropping, ending in a frenzy of self-adulation in the account of the Richards' Golden Anniversary: the whole transcript of the events: the junket in Ventnor, the congratulatory address; the half-page description of the illuminated text; the message from the Queen; the full attendance list for the London junket; the speeches there; "Mrs Richards' Happy Speech"; and the final presentation. It's quite exhausting.

into the water a red-hot iron block

Once you filter out all that, Almost Fairyland is an often interesting account of the personal, social and political events among the Ventnor elite in the late 19th century. Richards was a close friend of another incomer, the chemical magnate William Spindler, and both had a lot of ideas for Ventnor, which Ventnor collectively was largely tardy to carry out. Spindler got a lot of useful stuff enacted: developing a water supply for Whitwell, improving St Rhadagund's Church, building a new road off the escarpment avoiding the dangerous Whitwell Shute, and laying out Ventnor Park and Gardens. But he got fed up, writing a vehement A few remarks about Ventnor and the Isle of Wight aimed at the reluctant Ventnorians, and took his ball home to work on (unsuccessful) plans to develop St Lawrence. Richards writes:

He held the most uncompromising views as to controlling the seaSpindler died before doing much more, and his attempts to establish a sea wall and esplanade rapidly collapsed into ruins as 'Spindler's Folly'.

|

| William Spindler Crop of Bodleian Library 014642324 e-text. Licensed under Creative Commons CC BY -NC-SA 2.0: England and Wales. No commercial re-use. Any re-use must follow same license. |

|

| Proposed observation tower, Ventnor, I.W. Crop of Bodleian Library 014642324 e-text. Licensed under Creative Commons CC BY -NC-SA 2.0: England and Wales. No commercial re-use. Any re-use must follow same license. |

|

| Mrs Craigie Crop of Bodleian Library 014642324 e-text. Licensed under Creative Commons CC BY -NC-SA 2.0: England and Wales. No commercial re-use. Any re-use must follow same license. |

Almost Fairyland is illustrated with 53 monochrome plates. I rapidly spotted - compare and contrast ...

|

| Ventnor, looking west Crop of Bodleian Library 014642324 e-text. Licensed under Creative Commons CC BY -NC-SA 2.0: England and Wales. No commercial re-use. Any re-use must follow same license. |

|

| Ventnor, looking west Pictures in Colour of the Isle of Wight, 1910 |

|

| Ventnor, looking east Crop of Bodleian Library 014642324 e-text. Licensed under Creative Commons CC BY -NC-SA 2.0: England and Wales. No commercial re-use. Any re-use must follow same license. |

|

| Ventnor, looking west Pictures in Colour of the Isle of Wight, 1910 |

|

| Mrs John Morgan Richards Crop of Bodleian Library 014642324 e-text. Licensed under Creative Commons CC BY -NC-SA 2.0: England and Wales. No commercial re-use. Any re-use must follow same license. |

|

| Spencer and Sons, Ventnor Crop of Bodleian Library 014642324 e-text. Licensed under Creative Commons CC BY -NC-SA 2.0: England and Wales. No commercial re-use. Any re-use must follow same license. |

|

| Blake and Sons, Ventnor Crop of Bodleian Library 014642324 e-text. Licensed under Creative Commons CC BY -NC-SA 2.0: England and Wales. No commercial re-use. Any re-use must follow same license. |

|

| Rock Cottage, Ventnor, and coaching party Crop of Bodleian Library 014642324 e-text. Licensed under Creative Commons CC BY -NC-SA 2.0: England and Wales. No commercial re-use. Any re-use must follow same license. |

|

| The Richards' and Fulfords' Island coach drive Crop of Bodleian Library 014642324 e-text. Licensed under Creative Commons CC BY -NC-SA 2.0: England and Wales. No commercial re-use. Any re-use must follow same license. |

|

| Old Park, St. Lawrence, I.W. Crop of Bodleian Library 014642324 e-text. Licensed under Creative Commons CC BY -NC-SA 2.0: England and Wales. No commercial re-use. Any re-use must follow same license. |

|

| Governor Hans Stanley's Cottage, Steephill Crop of Bodleian Library 014642324 e-text. Licensed under Creative Commons CC BY -NC-SA 2.0: England and Wales. No commercial re-use. Any re-use must follow same license. |

|

| Craigie Lodge Crop of Bodleian Library 014642324 e-text. Licensed under Creative Commons CC BY -NC-SA 2.0: England and Wales. No commercial re-use. Any re-use must follow same license. |

You can access it through the Bodleian's catalogue - Aleph System Number: 014642324 - or through this slightly more convenient Europeana portal: Almost Fairyland, personal notes concerning the Isle of Wight.

- Ray